|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Map |

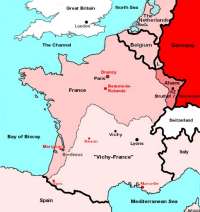

Some 300,000 Jews were living in France when the Germans invaded the country in early summer 1940. Many were French citizens whose families had lived in France for centuries and who were fully assimilated. Others had come to France, often from Eastern Europe, to seek a better life and escape from antisemitism. In the 1930’s, many German and Austrian Jews also sought refuge in France. After the German invasion, the northern part of France, including Paris, was governed by a German military administration. Most of the rest of the country (the "free zone") was ruled from Vichy by a government of collaborators led by WW1 hero Marshal Pétain and Pierre Laval. Alsace and Lorraine were incorporated in the Reich.

The Jews of France were required to register, and the usual restrictions on owning property and practising certain professions were introduced, as well as other signs of forthcoming persecution such as the marking of Jewish shops. The requirement to wear a yellow Star of David was imposed in June 1942. Jews who had been naturalised after certain dates were deprived of their citizenship, although many had children born in France who were therefore French citizens by birth. The Vichy government upheld far-right, authoritarian and chauvinist principles, and had strong antisemitic tendencies.

However, when deportations began in 1942, the Vichy authorities made determined efforts to protect French Jews from deportation, while leaving the Nazis free to do as they liked with nationals of other countries and stateless refugees. The Nazis in turn persuaded some of their allies, such as Romania, to agree to the deportation of their Jewish nationals living in France. (Italy and Franco's Spain, on the other hand, agreed to take back their Jewish nationals and would not allow them to be deported). Jews from occupied countries such as Poland or Russia were automatically "deportable". Ultimately, of course, the Nazis deported French citizens as well as other Jews.

The Jews of France were emancipated during the French Revolution, but France also had a long-standing political antisemitic tradition. The French Count Gobineau was one of the earliest antisemitic theorists, and the "Dreyfus affair" at the end of the nineteenth century was fuelled largely by antisemitism in the army and other leading circles of French society. In the 1930’s one socialist French Prime Minister, Léon Blum, was Jewish. He was kept at Dachau as a privileged prisoner during the war, but his brother died at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

|

| Deportation Camp Drancy |

On the other hand, the French population in general disapproved of the persecution and humiliation of the Jews. Leading members of the Catholic hierarchy condemned the treatment of the Jews. Monsignor Saliège, Archbishop of Toulouse, wrote a pastoral letter in their defence which was read in all the churches of his diocese (ironically, the outspoken Archbishop was an invalid who had lost the use of his voice years previously). France’s Protestant community was particularly active in helping Jews. As in other countries, special efforts were made to protect children. This contrasting situation was reflected in France’s response to the Shoah after the war.

Laval was hanged, but the apparently senile Pétain was simply kept in honourable detention until he died. After over 40 years of indifference, there has recently been a flurry of attempts to prosecute leading collaborators, such as French police chief René Bosquet (who was shot by a mentally disturbed person before he could be tried), or Maurice Papon who was responsible for deporting Jews from Bordeaux.

|

| Barbed Wire & Guard's Bunker |

|

| Brunner |

None of the three Germans principally responsible for putting the "Final Solution" into effect in France ever came to trial. Theodor Dannecker, who was responsible for Jewish affairs in the Gestapo in France until 16 July 1942, committed suicide in the American POW camp in Bad Tölz in December 1945.

Most deportations from France, including the four trains to Sobibor, took place under Heinz Rothke, born in 1913, who had previously been a military administrator in Brest. He had abandoned theology studies to become a lawyer and was a civil servant before the war. Rothke was apparently a workaholic and a ferocious antisemite who disliked personal contact with Jews. He had overall responsibility for the main French transit camp at Drancy outside Paris, but he seldom went there. After 2 July 1943 he was assisted by Alois Brunner, who in particular became effective commandant of Drancy. Brunner was also involved in the deportation of Jews from Wien to Sobibor (via Trawniki in the early summer of 1942. He took refuge in Syria after the war, and is probably dead now - all attempts to extradite him for trial have failed.

Both Dannecker and Brunner belonged to Adolf Eichmann's inner circle of "deportation experts" assigned to several countries; Rothke did not, but he was just as enthusiastic about deporting Jews. After the war he became a lawyer in Wolfsberg, Bavaria. He died in 1966. France never requested his extradition and, indeed, seems to have made little attempt to find him.

|

| Letter from June 1942 |

|

| Letter from March 1942 |

However, during the first months of 1943 the SS and their civilian contractors were attempting to make the new Crematorium II operational, and this was taking longer than expected. Moreover, there was a resurgence of typhus in the camp at this time. On the other hand, transports to Sobibor and Treblinka seem to have slackened during this period.

Richard Glazar reports that very few trains came to Treblinka in early 1943. Most of Poland’s Jews had either been killed or were being exploited for labour, and transports formerly expected from Romania and Romanian-occupied territory had not materialised.

Belzec ceased to function as a gassing centre at the end of 1942. Thus Auschwitz may have seemed overloaded, while Sobibor had spare "capacity". No doubt railway schedules throughout Europe and military railway and rolling-stock requirements also played a part in the decision.

|

| Letter from August 1942 |

All the victims were taken to the camp at Gurs.

Little or no attempt was made to separate French citizens from "deportables". Victims taken to Gurs from the camp at Nexon included Polish and Czech Jews who had fought for France in 1940 or were members of the Foreign Legion. One was a 65-year old rabbi. They were given five minutes to pack their bags. From Gurs two transports to Drancy were organised: one of 975 Jews on 26 February; the other, of 770 Jews, on 2 March.

|

| Jews in Drancy Courtyard #1 |

Convoy No 51: The 770 Jews transferred from Gurs on 2 March were joined by over 150 Jews assembled at the camp of Nexon. On arrival at Drancy they numbered 926 men, aged from 16 to 65, the majority aged from 37 to 45. Once again, many of these victims had fought for France; some of them had been decorated. 73 Drancy internees, including 39 women, were added to this contingent to make up the required number. The youngest member of the convoy, Victor Fiszban, was born in Piotrkow in 1928. Convoy 51 was also sent to Chelm, and then on to Sobibor. There were 6 survivors in 1945: Two of them, Mendel Fuks and Maurice Jablonsky, said that on arrival at Sobibor they were selected with a group of young people to go and work "very hard", and they at once set off again for Majdanek without entering Sobibor. Those selected were subsequently transferred to Auschwitz or Budzyn labour camp.

Convoy No 52: Convoy 52 comprised 640 men and 360 women. Over half the deportees, around 700, had French nationality, classed in various categories: French, French subjects, French by choice, by naturalisation and French by origin. Many of the victims of this transport had been arrested during a "clean-up" of the Old Port of Marseille which was carried out on Heinrich Himmler’s orders from 22 to 24 January 1943 to arrest "undesirables" such as petty criminals, prostitutes and, of course, Jews.

The 800 Jewish "undesirables", many of whom came from French North Africa, were taken to the camp at Compiègne. At the beginning of March it was decided to deport them, and on 10 March, 786 were transported to Drancy. 570 of them were French nationals. The Germans were particularly contemptuous of the Marseille Jews, whom they called "criminal scum", and the Jewish leader at Drancy also complained that they arrived virtually without luggage and stole from other prisoners. In fact these poor people had been arrested at night and given no opportunity to pack any belongings. Also included in Convoy 52 were foreign furriers and their families arrested on 18 March, following a request by Röthke to the Paris police. There were 12 children under 12 and 140 young people aged from 12 to 21. Warned in advance by Röthke that the convoy would be made up in majority of French Jews, the heads of the French police objected to taking part in organising the departure of the convoy.

In the end the French police gave in and cooperated, except that at the last minute the Gendarmerie did not provide the usual escort, which was replaced by 30 men from the German Order Police. The convoy left Drancy on 23 March, officially for Chelm but then went on to Sobibor. There were no survivors in 1945.

|

| Jews in Drancy Courtyard #2 |

3 of the escapees were still alive in 1945. When the train arrived at Sobibor, 15 deportees responded to a call for men who were prepared to work hard. Two of them were still alive in 1945.

One of the two survivors of Convoy 53 was Lucien Dunietz or Dunicz. He was born in Kiev but came to France to study chemistry at the University of Caen. He married a French woman, who was expecting their second child when he was arrested in the street in Paris in February 1943. He escaped from Sobibor during the revolt in October 1943. After the war he rejoined his family and they emigrated to Israel. He refused to speak about his experiences in Sobibor. In 1965 he agreed to give evidence at the trial of former Sobibor staff in Hagen, but he died of a heart attack before he could do so. He was 53.

The other survivor of Convoy 53, Antonius Bardach, came from Lviv (Lwow). He was first held in the camp of Mérignac near Bordeaux, before being transferred to Drancy, and then to Sobibor. He said the journey took about six days, with no food or water, in a sealed cattle truck which stank of excrement because he and his fellow prisoners were obliged to use it as a toilet. A young prisoner died during the journey. During Bardach's imprisonment at Sobibor he did a variety of jobs, including collecting the victims’ personal belongings and clothes and cleaning freight cars. He was beaten on many occasions, and suffered from hunger and diarrhea. After the revolt he hid in the woods near Lublin until the liberation.

See the List of deported Jews from the French Department Bas-Rhin!

In: René Gutman, Le Memorbuch, Mémorial de la Déportation et de la Résistance des Juifs dus Bas-Rhin (Editions La Nuée Bleue/DNA, Strasbourg, 2005).

The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names (Yad Vashem)

Photos: GFH

Sources:

Sir Martin Gilbert: FINAL JOURNEY - The Fate of the Jews in Nazi Europe (George Rainbird Ltd., 1979)

Serge Klarsfeld: Vichy-Auschwitz (Fayard, 1983 (Volume I); 1985 (Volume II))

Serge Klarsfeld: Mémorial des Enfants Déportés de France (limited edition)

Miriam Novitch: Sobibor, Martyre et Révolte (Centre de publication Asie orientale, Univertisé Paris 7, 1978 - testimony by the widow of Lucien Dunietz

Marseille, Vichy et les Juifs (Amicale des Déportés d’Auschwitz et des Camps de Haute-Silésie)

Personal communication from Serge Klarsfeld

Danuta Czech (ed): Auschwitz Chronicle 1939-1945 (Owl Press, 1997)

Jean-Claude Pressac: Les Crématoires d’Auschwitz (CNRS Editions, 1993)

© ARC 2005