|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1886, Father Andreas (Andrej) Hlinka, a Catholic priest founded the clerical People’s Party in Slovakia on an anti-liberal and anti-Semitic platform. Always seeking autonomy, Slovak nationalists looked on with admiration at the growth of fascist regimes in post WW1 Europe. By 1924, a paramilitary organisation, Rodobrana, the forerunner of the Hlinka Guard, had already been established. There had been a Jewish presence in Slovakia since at least the 12th century, and by 1930 a census revealed 136,737 Slovakian Jews, or 4.1% of the overall population. It has been estimated that at that time, around 50% of the doctors and 60% of the lawyers in Slovakia were Jewish.

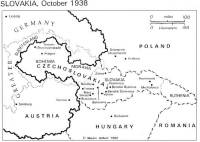

As the economic crisis of the 1930's worsened, the nationalist press launched a campaign against Jewish capital and members of the liberal professions. The People’s Party was especially vociferous in this regard. The aggressive policy of the Sudeten Germans ultimately led to the Munich agreement of 30 September 1938 and the ceding of vital regions of Czechoslovakia to the Reich. On 6 October 1938, Slovakia was declared an autonomous region. The Vienna Award of 2 November 1938 annexed parts of Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia to Hungary. Czechoslovakia was doomed; it had lost 30% of its territory, 33% of its population and 40% of its national income.

|

| Hlinka Guard * |

|

| Mach * |

Shortly after the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Slovakia entered WW2 as an ally of Germany. At the same time, even more stringent anti-Jewish laws were introduced in Slovakia itself. This process of identifying and isolating the Jews culminated with the implementation of the so-called "Jewish Code" on 9 September 1941. Jews had to wear a yellow armband bearing a Star of David. The star had even to be affixed to every letter sent by a Jew. The police were empowered to open such letters and destroy them. Based closely upon the Nuremberg Laws, the legislation imposed a host of restrictions on Slovak Jews, including a ban on intermarriage. In October 1941, Mach ordered the removal of 15,000 Jews from Bratislava, and by March 1942, 6,700 had been settled in Trnava, Nitra and Eastern Slovakia or were incarcerated in labour camps.

The Slovak government enthusiastically embraced the idea of deporting their Jews. In June 1940 they had promised to supply Germany with 120,000 workers. By October 1941 there were actually 80,000 Slovak workers in Germany. At that point, the Slovak government offered to substitute 10,000-20,000 Slovak Jews in place of the missing promised workers. At first the Germans did not respond to the offer, but shortly after the "Wannsee Conference" on 20 January 1942, Tuka negotiated the terms of an agreement whereby the Slovak government would pay Germany 500 Reichsmark for every deported Jew. For their part, the Germans agreed that the Jews would not be returned to Slovakia and that Germany would make no claims on the property abandoned by the Jews. The initial agreement had been for "20,000 young, strong Jews", but before their deportation had even started, Himmler proposed that Slovakia be made free of Jews. The Slovak government readily agreed. An intensive propaganda campaign was launched against the Jews. The newspaper Grenzbote" published articles praising the facilities and conditions of the Lublin region, for where so many deported Jews were destined.

|

| Registration in Zilina * |

|

| Deportation from Slovakia * |

By 20 October 1942, 58,645 Jews had been deported in 57 transports from the Patronka’s railroad siding and other places in Slovakia such as transit camps in Zilina, Novaky, Michalovce, Sered, Poprad and Spisska Nova Ves. Of the deportees, 2,482 were children aged four or under, and 4,581 children between the ages of four and ten. 19 trains, containing 18,746 Jews were sent to Auschwitz. 36 transports were officially sent to Naleczow, a station 20 km west of Lublin. Most of the transports arrived in Lublin, where young men were selected for work at Majdanek concentration camp and other people from the transports, mainly women with children and old people, were sent to transit ghettos. 2 transports with 2,052 Jews were directed to the transit camp at Izbica; from there they were sent to to Belzec and gassed. 8,000 of the deportees, mainly younger men, went to Majdanek, from where 1,400 were subsequently transported to Auschwitz. Among them was Rudolf Vrba (Walter Rosenberg) who escaped from Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. Vrba had been deported from Novaky on 14 June 1942. On arrival at Lublin on 16 June he, together with all males between the ages of 16-45, was selected for Majdanek, where he stayed until 27 June 1942 before being transferred to Auschwitz. In his memoirs, Vrba recalled how, in a cattle wagon with 80 other deportees being transported to Poland:

|

| Vrba * |

One of Vrba’s fellow deportees, Izak Moskovic foretold their future:

"You’re fools, if you think you’re going to resettlement areas. We are all going to die! Soon, in fact, he was forgotten, though later his words were remembered."

The young Slovakian Jews incarcerated in Majdanek provided the group of prisoners who basically built the concentration camp.

In 1942 they were to become the largest single national group of victims at Majdanek. Between May and September 1942, 2,849 of them died in the camp because of the appalling conditions, hard work, cruelty of the SS-men and a typhus epidemic. The latter was the cause of frequent "selections" in August and September 1942. Shortly before the Erntefest executions in November 1943, of the entire group of deported Jews from Slovakia, about 600 remained alive, most of them "privileged" prisoners.

The remaining Jews were distributed in a number of small towns and villages from which Polish Jews had already been deported. Most of the 24,000 whose ultimate destination was Sobibor were first sent to the ghettos in Chelm, Rejowiec, Opole Lubelskie, Deblin and Konskowola. After a few weeks they were sent to Sobibor for extermination. A small number of deportees were selected on the ramp at Sobibor and directed to labour camps such as Krychow, Sawin or Osowa. Within a few months they too were transported back to Sobibor and gassed. 5,000 initially sent to ghettos in Lubartow, Ostrow Lubelski, Miedzyrzec Podlaski, Lukow and Firlej were similarly re-transported to Treblinka and murdered after a stay of several months.

Among the Jews who were deported from Slovakia to the Lublin district were many highly educated people – doctors, professors and engineers. Most of them were not prepared for the primitive conditions that were prevalent in the small provincial towns of Eastern Poland. According to contemporary sources, there is much evidence to suggest that many of them died in the ghettos, because of the conditions existing there. Most of them did not know about the death camps, even those who were in the ghettos close to Sobibor, such as Rejowiec or Chelm. There are also sources which state that among the deportees, there were young people connected with the Zionist movement who attempted to inform other Jews from Slovakia about the fate of these who had already been deported to the Lublin district. In the Moreshet archive (Israel), there is an original report sent in 1943 from a small work camp near Sobibor, at which there still survived a group of the Slovakian Jews from three transports that had arrived in Rejowiec in 1942. The Slovakian Jews used their contacts with the members of the Polish underground for the forwarding of this report. The Polish underground also informed the Jewish organisation in Bratislava about the fate of the people who were in the ghettos in Opole Lubelskie and Deblin. Of more than 58,000 Slovak Jews deported to Poland in 1942, there were just 600-800 still alive at the war’s end.

|

| Camp Guards in Novaky * |

In May 1942, Eichmann visited Bratislava to inspect the progress of the deportations.

Some Jews were transported from the same departure points to the Slovak labour camps at Novaky, Vyhne and Sered. About 19,000 Jews – most of whom had certificates of exemption on the grounds that they were essential to the country's economy – remained in Slovakia. In addition, there were 3,500 Jews held in the three labour camps. Nearly 10,000 Jews avoided deportation by fleeing to Hungary.

The deportations ceased quite abruptly in October 1942. This was due in the main to the efforts of an activist group amongst the Jewish leadership in Slovakia. Named "The Committee of Six" and led by Gisi Fleischmann, through a combination of intervention with government and Catholic church officials, negotiations with the Nazis and bribery, they succeeded in halting the deportations. The Vatican, too, had begun to express concern about the fate of the deported Jews, and began to bring pressure to bear on Tuka.

Whilst the self-serving nature of his evidence must be recognized, during his post-war interrogation at Nuremberg, Wisliceny had some interesting remarks to make concerning the first cycle of deportations. Wisliceny claimed that the initial deportation of 17,000 single men was destined for labour, both at Auschwitz, where Birkenau was in the course of construction, and in the Lublin district. In May 1942, the Slovak government had requested that the families of those initially deported should also be sent to Poland, since their providers were in German hands. No arrangements had been made for the transfer of funds back to Slovakia and the families were dependant on the Slovak government for their maintenance. During Eichmann’s visit to Bratislava in May 1942, Wisliceny had accompanied him on a visit to Mach and Tuka, during the course of which an undertaking had been given by Eichmann that the Slovak Jews to be deported would be sent to the Lublin district (which most were) and that they would be employed in labour camps (which most were not).

|

| Alice and Hugo Elbert |

Eichmann said that a visit by a Slovak commission was impossible. When pressed for a reason, Eichmann evaded answering the question until, after much delay, he informed Wisliceny that Himmler had ordered the extermination of all Jews. When Wisliceny asked who was going to assume responsibility for this act, he alleged that Eichmann produced a written order signed by Himmler and addressed to Heydrich, which stated words to the effect: "The Führer has decided that the final disposition of the Jewish question is to start immediately." The order was dated either late April or early May 1942. For the present, Himmler had excluded from extermination those able-bodied Jews who were capable of work.

On 2 June 1942, (somewhat earlier than the date suggested by Wisliceny), Eichmann fobbed off the Slovakian government with an indignant note: an inspection visit had already been undertaken by the editor of an Ethnic German Newspaper, who had favourably described conditions in the camps to which the Slovakian Jews had been sent. The rumours circulating in Slovakia about the fate of the evacuated Jews were "fantastic" – the Slovak government had only look at the postal communications these Jews were sending to Slovakia. The deportations began again.

|

| Wisliceny * |

There followed a period of relative calm for the Jews of Slovakia, but with the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising on 28-29 August 1944, a second wave of round-ups and deportations began. To quell the revolt, Gottlob Berger, chief of the SS Main Office, was dispatched to Slovakia, together with Josef Witiska, as Commander of Security Police and SD, Slovakia and head of Einsatzgruppe H. Assisting Witiska was Alois Brunner, who had been responsible for the deportation of Jews from Vienna, Salonika and France. In late September, Berger was succeeded by Hermann Höfle, who brought in additional SS reinforcements, including the notorious Dirlewanger Brigade. The Aktion Reinhard camps had long since ceased operating and Himmler had ordered the killing facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau to be demolished on 25 November 1944. Because of these factors, an unusually high number of Jews from the second phase of deportations survived to the end of the war.

In 1945, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was resurrected, this time without the addition of Subcarpathian Ruthenia. The reborn Republic was to last until July 1992, when Slovakia again declared itself a sovereign state. During the post-war period, the majority of Slovak Jewish survivors emigrated, most of them to Israel. Today, of a population of 5.35 million in Slovakia (2004), about 3,000 are Jews.

Of the principals involved in the murder of Slovakian Jews, Tiso was tried and executed in 1947, Tuka was condemned to death in 1946, but died in prison and Mach was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment. Having given evidence for the prosecution before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, Wisliceny was extradited to Czechoslovakia, tried in Bratislava and hanged in 1948.

Deportations of Slovakian Jews to the Lublin District.

The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names (Yad Vashem)

Photos:

GFH *

USHMM *

Sources:

1) Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003

2) Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka - The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987

3) Gutman, Israel. ed. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990

4) Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of the Holocaust, William Morrow and Company Inc, New York, 1993

5) Wyman, David S. ed. The World Reacts to The Holocaust, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1996

6) Overy, Richard. Interrogations – The Nazi Elite in Allied Hands, 1945, Allen Lane, London, 2001

7) Niewyk, Donald L. ed. Fresh Wounds – Early Narratives of Holocaust Survival, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1998

8) Swiebocki, Henryk. ed. London Has Been Informed…Reports by Auschwitz Escapees, The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oswiecim, 1997

9) Vrba, Rudolf, Alan Bestic. I Cannot Forgive, Regent College Publishing, Vancouver, 1997

10) Kielbon Janina. Migracje ludno?ci w dystrykcie lubelskim w latach 1939-1944 (Migrations of the People in Lublin District). Lublin, 1995.

© ARC 2005