Memories of the Przemysl Ghetto

Aleksandra Mandel

"A Scream to the Sky"

So that those who perished may rise again

A grey, warm, and cloudy morning sifts in through the red-draped windows. I am lying on a narrow

bed by the window, looking at Mother’s bed. It’s already empty. She must have gone for potatoes.

She probably won’t buy much else for 10 złoty. There isn’t any more money...

In the other bed lies my Father. He seems so strangely small and haggard, all shrunken under the cover.

My brother Józef, a frail 20-year old boy, lights the fire under the iron stove. When Mother returns

they will both painstakingly grate the potatoes and prepare potato pancakes on the bare stove plate.

This will be their only meal until 3 PM. Then Mother will come to me at the Social Aid soup kitchen,

where I will give her some meagre soup or some burnt buckwheat groats.

I glance at the calendar. It’s July 15, 1942. Yes, it’s today. Today is the last day for all the town’s

Jews to move into the ghetto. The City Commissioner issued a decree saying that all Jews must

move from the city to this quarter by today. The decree was published 5 days ago. Those who

do not obey, says the poster, are subject to the death penalty. No Jew doubts the truth of the latter.

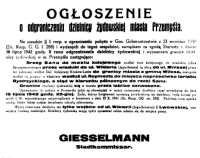

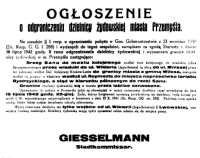

Announcement

About the delimitation of the Jewish Quarter in the town of Przemysl

On the basis of § 1 of the Decree on the limitation of stay in the General Government of 13 September 1940

(Journal of Decrees G. G. I. 288) and additional regulations issued thereto, I decree, as of 16 July at 8 AM,

with the agreement of the Starosta, the delimitation of the Jewish Quarter, whose boundaries are the following:

Along the course of the river San to the railroad bridge, along the rail tracks to the overpass

(Szczepanowskiego Street), from the overpass to Wiktoria (Jagiellonska) Street, along this street to

Mnisza Street over the rail tracks, along the Krakow to Lwów rail line to the city boundary with the Commune

of Wilcza, then following this boundary and, more precisely, following Reymonta Street to the point

across from the Bystrzycki Sawmill, from there in a northerly direction to the river San.

The boundaries of the Jewish Quarter are marked by signs in the field.

Jews authorised to reside in Przemysl are obliged to occupy an apartment in the above

mentioned quarter by 15 July 1942 at 10 PM.

Jews who leave their quarter will be punished as per § 4b. A similar punishment will be meted

out to those who consciously provide assistance to such Jews. The above mentioned quarter

will be accessible from Wiktorii (Jagiellonskiej) Street and Lwów Street. All other points

of access will be closed off.

Jews can leave the Jewish Quarter for the purpose of going to work.

GIESSELMANN

City Commissioner

We have been living in this quarter for 10 years. Garbarze is a quiet and green part of town

over the rail tracks, some distance from the town centre. It is a typical small town suburb, full

of the little houses of railway workers and the villas of retirees. We moved here when Tata’s heart

condition grew worse. The doctors prescribed calm, a ground-floor dwelling, and a garden. It

was so lovely and quiet at our place. Our modest two-room apartment was Mother’s pride: a

model of cleanliness, order, and cosiness, with well-kept windows covered with curtains, flowers,

and pleasant furniture from Mother’s trousseau.

Despite the long university years cheerfully spent away from home, there is no more pleasant place in the

world than this home of ours, contained in a small apartment. Perhaps this is because all of my love resides here.

In spite of my 24 years, no sentiment in me is stronger than my love for my parents.

For five days, carts loaded with furniture have been converging on the ghetto.

It is the first move of many to be ordered by the German authorities. People marked

with armbands drag their belongings.

They do not yet know that this is the beginning of the worst, so they want to bring everything:

furniture and utensils, glass and vases. The more well-to-do use flat-bed lorries. Poor people bring

their belongings in their own arms; sweating people carry their things on wheelbarrows and various carts.

Children carry dishes and flower-vases. The Judenrat, located in a school on Kopernika Street, is

besieged. The Housing Department somehow has to allocate space to all these people. The field

for corruption is wide open. The poorer people are embittered.

Sometimes one hears epithets: “band of thieves”, “Gestapo helpers”. The ordners (the Jewish

militia formed by the Judenrat) beat people with their nightsticks. Jagiellonska Street leading from

the city to the ghetto is completely jammed with people, carts, and wheelbarrows.

Our apartment has already been divided. One party gets the kitchen, while in the second room

there are other sub-tenants. We have been put into the tiny entry-way. There are four of us.

Tata has a very bad heart condition. Dressed in his clothes, he spends almost all day lying in bed.

The sub-tenants’ children make a lot of noise. They run through the room a thousand times,

slamming the doors. Father is upset and exhausted. I get up…I pack the pots into my bag,

put on a white apron, a white cap. I am a worker at the soup kitchen organized by the

Jewish Social Assistance (ZSS).

“You know, Lesia, they’re going to finish that wall around the ghetto today.”

“I know, Mama.”

What can we do? I have a ZSS identity document. And the ordners would let me into the town anyway.

“Yes, but why do you think they’re in such a hurry? What is it for?”

“I don’t know…”

I simply can’t tell my Mother that yesterday my colleague, Professor Ingber, said to me clearly:

“Behind this wall is our death. They’re pushing us all together so they can smother us at any moment.”

I consider Ingber to be a big pessimist. “Go on, go away,” I said to him with distaste, “You

sound like such a Cassandra. They won’t smother us. I heard that America…”

“Don’t talk to me about the protests of America and England – they’ll help us my foot.

Anyway, you’ll soon find out for yourself …”

I am by nature an optimist. I have a healthy constitution, I don’t give in easily to prevailing

moods. In any case, the struggle for existence – incessant and terribly strenuous – the struggles for

Tata’s injections, for fuel, for a simple piece of bread, deprive me of any perspective on the future.

My reality passes from the procuring of one piece of bread to the next. I need so little to be happy now -

a quiet night for Father without a heart attack, dinner somehow provided, so my family isn’t hungry.

That’s all I want...

“My brave child…” Tata says to me and strokes my hair. “I’m such a burden for you…” he adds quietly.

“Don’t talk silly. You’re everything to me. What would I do without you?”

I leave the house. I am carrying the bag with the pots and my slippers. At the soup kitchen my feet hurt terribly.

There are lots of people in the streets. All the attics, all the basements, every little nook and

cranny is crammed with people. The buildings no longer contain apartments but human anthills, destitute

of every – even the most primitive – conveniences. The gardens are ruined, trampled, filled with furniture

and bundles from which red eiderdowns poke out. There are papers, garbage, filth.

The Aryan Poles are leaving their homes to move into the city. The railway workers who

built houses here have grown accustomed to their little houses and gardens; they leave them

unwillingly, although they have received large "recompense" from the Jews, (who have given

up their own apartments), and although, Kramer, the Mayor, has assured them that they

will shortly return to their homes. I consider this a lie that is being spread to worry us.

Suddenly the ordners run into the street and drive the people away with their nightsticks,

shouting: “Giesselmann in the quarter! The Gestapo in the quarter!” I return home.

“Mama, don’t let Jozio or Tata go into the street today!”

I must be very pale because Mama gets annoyed.

The Soup Kitchen #1

“Why so panicky? You always get scared and frighten us. They’re in the quarter, and

so what? They’re always coming through.”

Embarrassed, I go out again through empty streets to the soup kitchen. From a distance, in

front of the Judenrat the green of our tormentors’ magnificent car stands out. What

do they want now?

The soup kitchen. A large, gloomy, brick structure with a stone floor and a giant fire, in

a foul-smelling, ruined courtyard full of sewer drains and children. It is situated right off the market square.

In front of the kitchen there is a long, dark corridor. Here, in the morning, workers gather before the

police and the overseers lead them off to work in the city.

The Soup Kitchen #2

Here we give them black coffee and 8 decagrams of bread. Here, in the morning, the air is full

of shouts and curses. Here they stand in line. Ragged, poor, marked with white armbands, with dinner

pails and bundles in which they try to carry something into the town to trade, in order to bring back

a few zlotys in the evening. As long as one lives, life goes on. Many of them might not return.

What is the life of a Jew worth? In the evening they come back for dinner. They curse that the

barley is dry, that the Judenrat members are stuffing themselves and giving the workers nothing.

And here they, who have been working hard all day under the whip of the Germans, under the

stick of a thug from the Baudienst, under the evil eye of a navy-uniformed boor, give way to

all their pent-up anger and resentment. Here, they too can demand something. Who is to think

of them if not the Judenrat? Do any of the gentlemen of the Judenrat go out to work in the

town, take lashes from the Germans, risk their lives? No, they sit comfortably in their offices,

overeating on chocolate and sardines. They play cards for high stakes! Robbers! Let them give

us a better dinner! Usually I try to calm such conversations, to explain, but today everyone is so

depressed that we serve breakfast in complete silence.

We are 30 women working here in two shifts. All intellectuals. Mrs. Reich, wife of a lawyer,

directs us. The work is very hard. We have to peel several cubic metres of potatoes, knead

noodles from several hundred kilograms of flour, scrub the floor, carry heavy tubs, clean the

sooty pipes, and run from the kitchen to the serving window, from the window to the section

validating food-stamps, remembering not to mix up the vessels, not to make a mistake in the

quantities of the portions…

I hate this work. Never before in my life have I engaged in physical labour. The steam is thick

and damp, a smelly cloud of odours from the poverty-stricken kitchen settles in my hair, in all the threads

of my dress. I have scurvy and in the heated air my gums begin to hurt terribly. And then there

are the shouts, the rushing to do it faster, to get it done.

Mrs Reich’s husband is a member of the Judenrat. We always get the freshest news from her.

“There’s going to be a contribution,” she tells us today. A contribution! Oh, that’s bad.

We know from other towns that all actions against the Jews have begun with a contribution.

“But it’s not certain,” she adds.

Maybe the Judenrat will somehow arrange matters. We seize on the idea. If it comes to

satisfying that insatiable beast – the Gestapo and the German magistrate – then the Judenrat has

means with which it might be able to arrange the matter.

“Please God that it may all end well!”

“Well, get to work, girl.”

I sit beside a basket of small semi-rotted potatoes and peel them automatically. My mind

returns to my home, to my Mother, whom I left without a penny, to my brother, who will certainly be asking for lunch.

Suddenly an ordner comes in: “You are all to appear at the Judenrat at two in the afternoon.”

What has happened? We are all upset. The ordner himself knows nothing, but he thinks that it’s the

contribution, that we have to give something. Give something? What can I give them? I am afraid of this

contribution, of these Germans in the ghetto. Something bad is hanging over us! Angry people flock in to dinner.

We hurry with the serving, we bump into each other, spill the hot soup; people curse. Everyone is talking

about the contribution.

No one knows how much we have to put in. A million, five million? The sum rises, the fear increases.

Something bad is behind it… Mama comes in, I give her a pot of our barley swill.

“Don’t worry, I might come back late. We have a meeting at the Judenrat about the contribution.”

At two we go to the Judenrat.

A school courtyard, once merry with song and noise, white aprons, and rows of children. Today it is

filled with garbage, cluttered with discarded school benches, and full of people with armbands. These

people, full of anxiety, are still unaware that here they will receive the first collective blow of fate.

Duldig, chairman of the Judenrat, arrives. Still a young man, fairly energetic. In my opinion, he

socializes too much with the Germans. Others claim that he has to do it for our sakes. Perhaps.

He says that they require a two million zloty contribution from us: that we have to give up everything

we have if we want to continue to exist.

The end of his speech terrifies me: “If only the Jewish workers alone remain, it is worthwhile for

us to give up everything we have.” His hoarse, low voice, echoes lamentably from the walls: “If the workers remain”…

the sentence keeps returning to my mind. I think about my brother, who never works, about my sick and helpless

Father. What will I do with them? O God! What will I do with them?

After Duldig, Boldman, the tub-thumper and careerist, speaks. He approves of one thing and he

doesn’t agree with another. He bangs with his fist on the table. Caught up in my thoughts I can’t follow the thread

of his discourse. I know only one thing: that something bad has happened and that the Jews must give the

Germans what they want. And that even if they give everything they have, something horrible is going to happen.

And that only those who work will have a certain chance.

The gloom continues. Some lady throws a gold chain on the table, someone pulls a ring from his finger,

someone lays a gold watch down. I look at this strange, despairing outbreak of sacrifice: that growing

pile of precious objects is the price of our lives.

Anyone at that moment would give his last shirt.

The words of the chairman about the workers won’t leave my mind, while the chairman is

already dividing people into twos to go through the streets with a member of the Judenrat or ZSS and an

ordner. For any abuses – the death penalty: that death that is getting closer to us today, standing face to face

with us. Careful! It seems so close that it would be easy to stretch out a hand to touch it… I go with my neighbour,

Lola Laub. She lives in the same house as my family, and we work together in the kitchen. I am very fond

of her; she is so good to me. She always improves the hopeless afternoons in the sweltering and stifling

kitchen by giving me some tasty item. She is elderly and childless, and treats me like a little girl.

We cross the stone bridge on Jagiellonska Street. This part of the Jewish quarter, which we have to

cross with the contribution list (we are carrying a list already prepared), is located just beside the entrance

gate to the ghetto. A mass of workers are busy building a high wall. We can hear the gloomy thud of

hammers; the rough lumber is placed across the opening of the great gate. When the gate closes, the world

will be entirely cut off. I try not to think about any of it. In any case, we are beginning to go from house to house.

Hundreds of pigeon-holes, hundreds of tidy kitchens, little rooms, partitions. And everywhere

people in armbands. Ailing old ladies, grey-bearded elders, overworked women, quiet children, and

everywhere the same terrified question – what will happen? What will happen?

Not everyone wants to give. Some offer twice, three times as much as asked, others argue and dicker.

The more resistant we send with the ordners to the Judenrat.

I am ruthless. I take from the old and the young, the healthy and the sick, from everyone. It’s a matter

of life and death, it’s no joking matter, they have to give and they do give. They give… Our briefcase fills with

money, with valuables. We write out the receipts quickly.

Evening falls. A dying old woman pulls her wedding ring off her finger. She hands it over and curses

the Germans: “Accursed nation, they won’t even let me die with my husband’s ring.”

There are ever more rooms, more niches; outside it grows darker while our hearts grow sadder

and sadder. Give, give! It’s a matter of life and death! “No hurry,” says an ordner “this time the

Germans are allowing us to go about all night.”

But I want to be at home, among my own people. We are finishing. The last house – an anthill.

Sad, swarming with people and with the heavy air of the carbide lamp trying to drive back the darkness.

It’s Friday evening. As tradition requires, the good hands of a mother are lighting the candles. Thus it

was a thousand years ago, and so it is now, in spite of the forced contribution, the ghetto, misfortune, and beatings.

Done. We have a good sum. By side streets, through dusky courtyards, we return to the Judenrat.

There is a terrible bustle. The office is jammed with people still bargaining, explaining, bringing valuables.

The office is full of money. The ringing sound of coins mixes with loud counting. It’s a sort of horrible,

monstrous exchange, in which we are trying to trade money for our lives.

We give our list to the chairman. The money tallies. We return home. Of course, there are no

Germans in the streets, but, distrustful, people remain hidden in their houses. We cross a green square –

empty and grey in the moonlight. We turn into a small street, our street. The lights are on at our house.

Through the red curtains in the window a weak light falls on the dead street. For as long as the light

shines through the window of this house, my life is worth something, I think, touched with a strange foreboding.

In the house Tata and my brother are already in bed, but not asleep. Mama has kept the fire in the

cooker; she gives me warmed-up soup. A small candle gives off a weak light. I tell them everything except

Duldig’s words about “the workers remaining.” I say that even in those small, wretched rooms crowded

with people, it was clean and neat, and that it was wrong to say that Jews are dirty. “It’s Friday,”

says Mother, “they have scrubbed and baked.”

I toss in my bed and can’t stop thinking. It’s night, a summer night. The stars are shining quietly,

as they always shine in July, but my heart is very anxious. I must – I have – to do something, I have to

get my brother in somewhere, so that they give him a work permit. Mother has a modiste’s diploma,

at one time she studied that trade. Now it might be of use. Father is seriously ill. If we three are

accepted as workers, maybe he can stay with us.

Tomorrow I have a day off. We work every other day, two shifts in turn.

Above us, on the first floor, lives Dr. Tennenbaum. I know him from university days, when he

was a bachelor. Today he is a director in the German Employment Department and is master of life and

death so far as Jews are concerned. Maybe I can arrange something for my brother through him. “All right,

find an artisan who will take your brother as an apprentice, and I will issue him a work card.”

I take my brother’s papers; I have difficulty getting the ordners to let me into the city. I tell them that I’m

going to the hospital, to sick people, on the orders of the ZSS. The police aren’t standing by the gate yet.

I run to P, an engineer. He is an old party acquaintance of my father’s, a good, honest man.

He agrees at once to give my brother an apprentice’s card. “After all, I worked with your father for

20 years in the Party,” he says simply, although he knows what he is exposing himself to in issuing a false

document. I am moved. I sit in their beautiful salon, a spruce room in good bourgeois style. In another room their

young daughter patiently and industriously practices a Clementi sonatina. P’s wife is already in bed. Their life

breathes calmness. Not like at our place, not at all…

Arbeitskarte

The Employment Department is located in this same street. Tennenbaum takes the document from me.

He will bring the work card to me at home in the evening. I am very glad. I think that my brother is out of danger

now. I’m on Slowackiego Street. A little higher up is the Jewish cemetery, where my grandmother was buried

during the winter. I think back to her wretched funeral: that little coffin on the rickety cart, Mother and I following

behind. I go to the cemetery. Furtively and uncertainly I sneak along the streets. I have an armband on a white

overcoat; it doesn’t stand out much. I’m not at all a Semitic type, so the Germans pay little attention to me.

But when I get to the gate of the Jewish cemetery a group of tatterdemalions shout at me: “A Jewess, a Jew-girl!”

I am not surprised at them. In these times, when Hitler has condemned us with hatred and contempt…I am

no longer a well-dressed young woman, not a person with a university degree, not a person at all. A year and a

half of the Nazi regime have taken from me, in the eyes of the local rabble, all right to humanity. At this

moment I’m just a Jewish girl, someone whom one can spit on and throw rocks at with impunity.

Gravestone

It’s quiet and peaceful in the cemetery. Fat insects crawl over the grass. The old stone grave markers tell the

histories of former families. The gold letters of the shining sepulchres call to those who have gone and assure

them of the impeccably good taste of those who have remained. My grandmother’s grave is off to the side.

In the beaten clay a black marker has been stuck. ‘Klara Mann, born… died 12 XII 1941’... a beginning and

an end. I stand by my grandmother’s grave but I do not cry. I am not thinking any more of her lonely

death. She loved me so much. In my thoughts I beg her to help me rescue my parents and my brother.

I don’t even have a flower to lie on her poor grave. People in armbands are not allowed to walk the streets

with flowers in their hands. It’s a provocation to the Germans.

Several days pass. The feeling of threat increases. From Lwow, from Tarnopol comes news about transportations

and letters full of hints and warnings. Mama tells me about a letter in which it was clearly written: “When the heat

wave comes, sit in the shade.”

“What does that mean, Mama?”

“I think it means that we should hide when there is a transportation.”

“Eh, I don’t suppose they’ll transport us – I’m working, Jozio has his work card. You’re a modiste.

As to Tata – I imagine a family has a right to one non-worker.”

“Let’s hope so,” says Mother without conviction.

I wonder why the Judenrat is calling such frequent meetings of the ordners. The subjects of these

meetings are supposed to be secret, but by a strange coincidence, when the ordners leave the meetings and

go through the ghetto, the most horrible rumours spread about. That there will be an ‘action,’ that it will be

merciless in spite of the contribution and supplement paid, that the workers will remain. That no one

should dare hide, because the Germans will go from house to house with dogs and are going to shoot

anyone who is hiding. That those who leave will get jobs in villages. That those who stay will envy those

who leave. Duldig is doing something. The Judenrat is doing something. The Gestapo is doing something.

The machinery has been set in motion. The first victims would soon be caught in its meshes. As usual, I am

absorbed by my primitive struggle for existence. I don’t think about the danger, I think about bread and potatoes;

about my Father, who looks worse and worse and who leans so hard on his cane when he takes even a few

steps. But he is full of hope. Someone from the Judenrat said to him that even if it became necessary to

send off several thousand people, “you, an editor, we will surely not touch. The matter is in our hands. There

are so many outsiders here.” Tata has always believed people.

The Henners are our neighbours. He is an elderly gentleman, a goldsmith, a cultured merchant; she, a very kind,

gentle old lady. Two of their sons have been killed in the war; the third son, a doctor, lives with them together

with his father-in-law. This doctor is my friend and confidant. It is on his door that I knock in the middle of the

night, when my father has heart problems; it’s he who advises me in all matters.

Together we consider the meaning of the latest incidents. He tells me that in Krakow the SS are arguing

with the Wehrmacht, who oppose the transportation of the Jews, and therefore the action won’t even begin

here against us. I’m so happy. I run home with joy and kiss my Father. I take my brother and go out with him

for a little while. The boy’s life is so hopeless. Suffering from nervousness, incapable of working, he is our

Mother’s greatest love. This tall, delicate, hunched brother has never stopped being her little Jozio, who

has to be protected and sheltered from the world. And Mother protects him with the ferocity of a lioness.

She has protected him from the army, from forced labour, from jeers and name-calling in the street. I love

him too. Whenever he goes out alone, after a moment I run out after him, asking people if they’ve seen him.

Father calls it craziness. But he’s my brother, my only brother. We always go everywhere together. I could

not enjoy any pleasure without him.

We walk along the hot little street, between the small dusty gardens, and reminisce together about the

good old times – the times when as free people we had access to the whole world. We remember 1939 and

our stay in Skole, from whence, alarmed by news of the approaching war, we hurried home to be with our parents.

“Jozio,” I suddenly ask, surprising myself, “would you stay with me if it turned out that Mama and Tata had to

leave?” The last word comes out of my tight throat with difficulty.

“No. If they went, we would go too,” my brother answers quietly. “I would not stay without Mama,”

he adds after a moment. Yes, and at that moment it is clear to me as well that if we go into exile – we all go.

The Action

Work in the soup kitchen is getting ever harder. There is a sticky heat wave, full of steam and kitchen fumes.

We are all irritable from the uncertain situation. Quarrels break out at every moment. We sell a cupboard

and have a few zlotys in the house. At least I don’t have to worry that they are hungry.

“There’s going to be a big transport,” Mama tells me when she comes to get dinner. “They’re going

to take everyone. They’re going to go from house to house.”

Lord have mercy on us! From this grave, nailed down with boards, there is no way out, no escape.

People keep bringing ever fresher news. The Schutzpolizei have surrounded the quarter! They’re closing

off the square near Iwaszkiewicza Street with barbed wire! I pass through that square, which lies near my house, ten times a day.

Today a thousand people are brought in from mountain regions; they’re being put in barracks. Indeed, in the

evening they come with great kettles for food for these people who came from the mountains, and who are

going to go on in the coming days. To work, the Judenrat assures everyone.

When are they going?

Where are they going?

Why didn’t they go straight to their destination?

I place dark noodles at the bottom of a large pot. I pour gooey soup over them, and all the time

my thoughts constantly turn towards those people housed in great, empty barracks, brought from some

distant mountain village, who are waiting here to travel on.

Suddenly a thought cuts painfully, like lightening, across hesitation. And I know, I know now what they are waiting for.

They are waiting for the action in Przemysl.

In despair I try to protect myself from the thought. Didn’t Henner tell me that they wrote from Krakow…?

No, no, nothing will happen.

As usual, my unreasonable optimism gets the upper hand over reality. I return home. Evening falls early.

Navy blue clouds hang in the sky, swollen and threatening. Nature has grown oddly quiet. People in

armbands go about confused and perplexed. A German car is standing in front of the Judenrat again.

Once more the ordners are driving the crowd away.

But life goes on. The little shops set in the wooden partition and the small wooden huts are full

of goods. Flour, sugar, butter, candies and pastries. I would so gladly buy something for my Father. I

do so like to bring home pastry for my parents. My Father pretends to get angry with me, saying that I

spend money unnecessarily, but later he eats with touching gluttony.

Unfortunately, I haven’t a penny.

And here, in spite of the wall cutting the ghetto off from the world, there is food of all kinds.

Jews are clever. They even have the ability to organize trade based on an unlikely event.

Other than the privately-owned little shops and booths full of goods at black-market prices, there

are several official shops in the quarter. In these shops, the poorest people receive bread every week by

ration-card. 50 decagrams per head is apportioned to them by the Judenrat. And for this miserable portion

the poor crowd and push in a long, snaking, clamorous line that blocks the street.

And now, towards evening, the poor stand in front of the shop for their bitter daily bread, apportioned

by German ‘philanthropists’ and considerably reduced by the insatiable board of the Judenrat.

I spot my brother in the line. Thin and bent, he tries to reach the shop. An ordner thrusts him down the stairs.

I can’t watch. I run and take the ration-card from my brother. The ordners know me. As a member

of the ZSS I can go anywhere without waiting in line. I think with bitterness that even in this hell, in this “ghetto

of the damned,” a protection system exists. And for what? For a miserable 50 decagrams of bread.

At home the mood is quiet. Tata, the great politician, gives us the news from the distant world, conclusions

derived from Krakauerka, or brought by secret routes from the radio, which someone working for the

Kreishauptman himself heard with his own ears. From the news it appears that Hitler is sure to lose.

That news is continually making the rounds in the ghetto. Nowhere, probably, is Hitler’s defeat, at the

moment of his greatest victories, so much a foregone conclusion as here…

“What does it matter,” says Mother. “I don’t know anything about politics, but you’ll see,

before they crush him, he’ll send us all to die.”

Then Father tells Mother something I will remember later, in the most difficult situations: “Tough.

At this moment we are fertilizer for history, but Hitler’s defeat is certain. He has to swallow what he’s

bitten off. As for us – we’re not important…”

To turn my Mother’s sad thoughts to other things – my Mother, who is so bravely bearing the

burden of our poverty – I hug and kiss her, and talk to her about my uncle, who from far, from Africa,

writes to us through Switzerland and who will certainly help us as soon as the war finishes.

“And you, Mama, will be the first great lady of Africa, and Tata and Jozio will eat bananas for

breakfast and pineapples for dinner.”

Mama looks around at our shabby little room, at the lamentably empty cupboard, at the unlit stove,

and says: “Child, you might see it, but my grave will be growing grass by then…”

The days pass one after the other. Nothing new is happening, but dreadful rumours circulate

about transports, about actions, about pogroms in little towns. All of this is vague, without definite facts,

but it’s sufficient to create a feeling of danger and the worst forebodings in our care-laden hearts.

They are taking ever fewer groups into the town to work. Aside from this small number of workers

no one is allowed to pass through the gate of the ghetto any longer. The place of the ordners at the gate

has been taken by the Polish police. A poster states clearly that any Jew caught in the town will be shot at once.

But somehow people make do and the ghetto retains the appearance of normal life.

It is Saturday morning. A hot, July day. Somewhere in the world, and not at all far from us – just

on the other side of the wall – people are living normal lives. On the banks of the San River, on the

beaches, they’re sunbathing and swimming. There’s the Castle, for example – so pretty in the green

park. The children run through the streets. Housewives let down the blinds in the windows so

that their plush furniture won’t fade, and then the apartments breathe with a sweet coolness.

The thought that beyond the wall there is freedom and life takes away from me all desire to work,

all desire for any sort of effort.

I’ve always prized freedom so highly. I’ve never believed in force; it has always disgusted me.

Out of respect for other human beings, I have never in my life humiliated anyone. And today I am the

worst of prisoners, an animal locked behind a wooden barrier.

But the feverish work in the soup kitchen doesn’t allow for very deep thoughts. In the morning

we are told that we are going to Dr. Aberman, to the Judenrat to be vaccinated against typhus.

Only out in the world is it warm, blue summer. Here, where people wear armbands, life is

poverty, crowding, dirt, and typhus, with which one has to fight profilactically.

Suddenly, in the afternoon, they call off the protective vaccinations. I am so glad that I will avoid the

pain of the shot, that I don’t even wonder why the vaccinations were cancelled.

In the evening I go home. The air is clear in the blue sky. Here and there a bit of greenery makes it way

out from under a stone cobble. What a difference between the calm of the early evening hour and the

despairing anxiety in our hearts!

During these last days the Germans have divided Targowica Street into two parts with a wire fence.

The barrier even cuts the road off from the Jewish quarter. The soup splashes in the pot, spilling over my

bag and splattering my dress. Everything is difficult and sad. On the other side of the fence I suddenly see

Schutzpolizei men standing. They weren’t here in the morning. It’s not a good sign. Something is

unquestionably imminent. Maybe something will happen this very night – fear squeezes at my heart.

They stand tall and threatening in their helmets. One careless gesture on this side of the fence and a

bullet ends a life in a blink. Suddenly, beyond the fence, a car stops. It came so quietly from the direction of

Zasanie that I did not hear it at all. Now it is standing beside me, at the distance of a few steps. Three pot-bellied

Gestapo agents get out of the car. They gesticulate and distinctly point towards me. I stand like a statue

on the sidewalk. The street has instantly grown empty. I am alone, and a few steps away, beyond the fence,

three torturers, laughing and conscienceless, are gesturing towards me, telling me to come near.

What will they order done now? Will they shoot me? As usual in a moment of extreme terror, a thousand

thoughts fly through my mind in a fraction of a second. No, they aren’t shooting.

They ask me where the square is on Iwaszkiewicza Street. I tell them that they have taken the

wrong direction. I speak German very badly.

I drag myself home and recount my adventure. Mama says, “Something like that could only happen to you.

They can tell even through the fence that you are terribly afraid of them.”

Mother is right. I am terribly afraid of them.

I sit down with my brother in the small garden whose stone courtyard was, in quieter times, the

object of the gardening efforts of the entire building’s inhabitants. Today it is uncared for, overgrown with

weeds. The greenery attracts me, however. I am very much in need of some relaxation, even for a moment.

And today Mama’s flowerpots are standing here. It spite of all the cares of the day, Mother never forgets

to water and trim them.

I sit with my brother. I like to talk with him. He confides to me that just as soon as the

war stops he will get to work.

“You see, Lesia, now I’m not suffering from my nerves at all. I’m going to work like any normal

human being.You’ll see. I’ll relieve you.” He tells me everything about his modest plans. He wants to be

an assistant in a library. He likes to read a lot.

“Fine, Jozio, maybe it will really end. They’re always saying after all…”

I don’t finish the sentence because Mama runs into the garden, out of breath. “Listen, the Judenrat

has announced the stamping of work cards. People are running to the Judenrat. What does it mean?

Run – find out what it’s about.”

I run into the room for my document from the ZSS, the blue identity document with the photograph.

I knock at the Henner’s. The doctor opens the door.

“Doctor, what does this stamping mean?”

“It’s the beginning of the action,” he answers quietly.

“Doctor…”

Like a fast-forwarded film the thoughts run through my mind: the cancelled vaccinations, the

Schutzpolizei men beyond the iron grate, the car with the Gestapo agents – and further words die in my throat.

I run into the street. A thousand people are already running to the Judenrat. There is a great panic.

A hundred rumours, each one worse than the last, pass from one person to the next. And as the news passes from

one mouth to another it becomes more and more terrible: that this very night they will go from house to house,

that they will collect everyone and shoot them on the spot. Everyone is running, old and young, workers with

children, ordners and Judenrat members. In front of the Judenrat the sombre crowd beats on the gates to the

building. But the Judenrat is already closed. And now no one is talking about the cancellation of the transports,

about the protests of the Krakow SS, about Hitler’s sudden defeat. People run around the closed Judenrat,

panicked, terrified of the coming night, of the stamp they can’t get, of the future, where death is baring its teeth at them.

Dr. Henner and I can’t get into the Judenrat either. Besides, I’m not in favour of remaining all night

without my identity document. Maybe it’s some sort of trap. Maybe they will take those who don’t have

employment documents. Dr. Henner agrees with me.

We go home through streets filled with terrified, feverish people.

Ordners are coming out of the Judenrat. I ask one of them what it’s really all about with that stamping

and whether we should give up our identity documents.

“And what do you think, you want to go off with that unstamped document? What good will it be for you?”

I don’t understand very well the sense of these words, but I don’t go back to the Judenrat. I decide

definitely to keep the document with me through the night. I think that if they come in the night, then maybe it

will somehow help me. Up to this time the Germans have rather respected the ZSS.

Tata is relatively the calmest of us all.

“Do you think I’m so much in need of life? It’s not worth anything anyway.”

Troubled, we lay down in our beds, but aside from Tata, none of us sleep. I lie beside the window and

carefully catch every rustle coming from the street. “Mama,” I whisper quietly, so as not to wake my Father,

“I hear some steps.” The steps come closer, measured and heavy.

“They’ve come,” answers Mama in a breathless whisper.

The steps stop under our window. A flash lights the number of our house. In terror I stop

the breath in my chest, as if I were afraid that it would pierce the wall and the glass and reach those lurking under our window.

Someone beats on the window, once, twice.

“What shall I do, Mama?”

“Open it, otherwise they will shoot.”

My hands tremble. I kneel on the bed. Nervously I push away the curtain, struggle

with the stubborn window frame. With relief I see that it’s only ordners.

“Why do you frighten people in the night? What is it?” I ask angrily, glad in my soul that it is only ordners and not those others.

“Give us the work cards for your entire family to be stamped. The Gestapo are stamping them

in the Judenrat. By morning everything has to be stamped.

I give them the papers and ask: “Will everyone get stamps?”

They don’t know.

“What will happen to those who don’t get them?”

“We’re only supposed to bring the work cards to the Judenrat. We don’t know anything more.”

They go away. Mama and I lay awake until morning. I can’t wait for dawn to be able to go

out and run to the Judenrat. After a long and anxious night, the room at last grows brighter in the

grey early morning light. My Father and brother are sleeping quietly.

In the Judenrat they have been working all night. The Judenrat members, inaccessible and busy, run

back and forth with piles of work cards,. The ordners are not allowing anyone into the chairman’s room.

But the situation is already entirely clear. During the night only certain work cards were stamped; those

can be picked up in the Judenrat’s secretariat. The unstamped ones will be given back by the ordners in the garden opposite the school.

The action is foredoomed. No one deludes himself any longer.

My work card has been stamped. But only mine. Neither my brother’s nor my Mother’s was stamped.

I have a lot of acquaintances and the nearness of danger makes me seek some help, some form

of rescue from them – perhaps something can still be done.

“Why didn’t you have your ZSS document written out to your Father?”

“To my Father? But he isn’t working, I am.”

“Yes, but you could have done that, and then your Father would have covered you all.”

I hear these words and feel a terrible pain. No one told me. Who knew that it was possible to do that?

Now it turns out that the Judenrat members knew everything. And the ZSS functionaries also. But they kept it a secret.

Now I begin to understand why in recent times so many ladies, whose husbands were doing very well

financially, came pushing into the soup kitchen as ordinary workers to do heavy work.

It was all arranged beforehand by the Judenrat. Like someone possessed, I run from office to office, from

one acquaintance to another. I beg, explain, curse, to get them to change the document and write it out for

my Father. My Father is ill; he worked so many years for the city. Do something, save him!

Too late, nothing can be done!

I run home for my Mother, I drag her to the Judenrat. But I’m not the only one running and going mad.

A thousand unstamped people are running despairingly around that barred trap, hedged in by the horrible

mugs of the Gestapo agents.

And it’s a Sunday morning, warm and sunny. From the town comes the sound of church bells.

Along the railway lines, visible from the Judenrat windows, a shiny train runs quickly past.

The world goes on in its usual form. Only we, the condemned, on that clear Sunday morning, are

being pushed by the hand of a merciless fate off the ledge of life into the chasm of death.

We’re whirling about here for nothing, in this monstrous inferno. Infused with the universal instinct for life,

we seek in vain to turn fate aside and somehow wriggle free.

After 12 noon, people without stamps are not allowed to walk in the streets, states a notice on the Judenrat.

I go with my Mother, leading her by the hand. She is so poorly dressed, in black stockings…in the full

sun I see how the poverty of this last period has diminished her.

With difficulty we squeeze through the crowd in front of the Judenrat. In the open windows of the ground floor

stand the functionaries – the children of protection, all with stamps, and they are giving the workers – who worked

so hard for the Germans – the sentence of death: unstamped work cards.

The name of my brother is called. I take his document from the hand of a round, red-faced functionary.

He directs the Ernährungsamt. He gives us rations from the soup kitchen. They say he’s already made quite a fortune.

And this ox, feeding off the exploitation of the unfortunate, has received a stamp, and my brother hasn’t.

If I could, I would strangle him with my own hands, without a scruple.

My Mother’s help is of no use. No one even wants to listen to her.

At one time all these authorities of the Judenrat strove for a smile from her, a kind word. She was known

for her beauty and wit. She was the queen of all the balls. I was already grown and my mother was still receiving homage.

Today – shrunken, poverty-stricken, with regrettable grey veins on her nose, she requests the

chairman to do something for us.

“My husband and I are of no consequence,” she says, “we’re old anyway. My daughter has a stamp.

Do something for my son. He’s a young boy, he hasn’t lived yet, let him remain.” Even at this moment my

Mother doesn’t think of herself. Her heart is filled with concern for her son.

The chairman’s answer is like a blow in the face:

“We have more valuable people than your son and we can’t do anything for them.”

My Mother leaves the Judenrat. Her back is slightly bent, but she walks quickly, not looking around.

She is going back to her duties. And although her heart is filled with the most terrible pain, the pain

of a mother whose most beloved child is condemned to extermination, she stands bravely by the small, iron

cooker and cooks some sort of hot meal for us. A heroine, a heroine of a terrible fate. But I still haven’t given up.

I run from floor to floor. Hundreds of people are running about as well.

Maybe they will stamp the artisan’s cards separately. Someone said something about such a

registration. Yes! Yes! They are already writing out the register of artisans. And a thousand people

already know about it. They trample each other in the doors leading to the artisans’ commission office.

I put in my brother’s card and my Mother’s modiste diploma.

Maybe it will work, maybe!

It’s afternoon. I have been in the Judenrat since five in the morning. I haven’t eaten anything since yesterday evening. I’m terribly hungry.

At four they are going to return the artisans’ cards. I go back home. It’s quiet in the streets already. People

have used up their energies, their ideas. They wander about sad and extinguished. The little shops are closed.

A merciless heat wave falls from heaven.

At home, my Father and brother don’t completely understand the situation. My Father tells me that I look

awful, that I should lie down. I’m not thinking about myself.

Through the open window comes a conversation in the street: “Have you got the stamp?”

“I haven’t got it. Maybe my father will get it.”

The Nazi thugs have squeezed the entire circumference of the globe down into the small circle of a stamp.

Our life is enclosed within that magic circle.

The Gestapo stamp – to be or not to be.

At three, Dr. Henner comes in. He is pale and has a worried face. I know from the outset that

he is bringing bad news. He pulls out a piece of paper. It’s already being plastered on

walls. Tata reads the German: “All Jews not possessing stamps will be moved to a new area.

Permitted baggage – 10 kg. Bread for two days should be brought.”

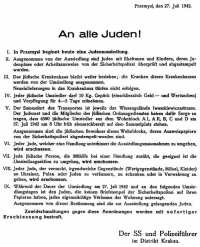

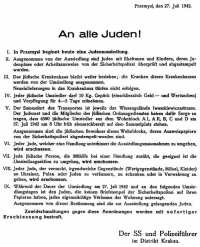

To all Jews!

I. Today in Przemysl the resettlement of the Jews (Judenaussiedlung) is beginning.

II. Resettlement concerns all Jews, their wives, and children, whose permits and work cards have

not been checked and stamped by the security police.

III. The Jewish hospital is still functioning. The hospital patients are not subject to resettlement.

There will be no further admittance to the hospital.

IV. Each resettled Jew may bring with himself 10 kg. of baggage (including money and valuables) and food for 4-5 days.

V. The collection point is the square on Iwaszkiewicza Street. The Judenrat and members of the

Jewish order service are to ensure that the 4,500 Jews to be resettled from settlement AI, AII, B, C, and D,

should be standing ready at 8 a.m. 27 July 1942 to march to the collection point. Those Jewish residents

of the settlement whose documents have been stamped by the security police are excluded.

VI. Any Jew who tries to avoid resettlement will be shot.

VII. Any person of Jewish descent who receives help for the purpose of avoiding resettlement, will be shot.

VIII. Any Jew who attempts to give, or give into the keeping, of a Ukrainian, Pole, or other Jew any

sort of goods (valuables, furniture, clothes) will be shot.

IX. During the period of resettlement, 27 July 1942, and in the course of succeeding resettlements, it is forbidden

for any Jew not possessing a police stamp in his documents to leave his place of residence.

This regulation does not concern Jews subject to resettlement.

Any action countering this decree will be punished by immediate death by shooting.

The SS authorities and Police in the district of Krakow

I burst into awful, loud sobs. Never in my life have I cried so loudly. I have the feeling that this awful

German order, read by my Father, has struck into my heart. The tears that stream from my eyes are not tears

but blood soaking out of my torn heart. Never have I felt such despair, not even when Tata was very ill.

I beat my head with my fists, the pain convulses me in a paroxysm. Tata hugs me. He has tears in his eyes himself.

Mama says, “She will remain anyhow, but we, but Jozio…what will happen to us?”

Again I cry. It’s not tears; it’s the howl of an animal whose young are being pulled out of the den.

“You don’t know how to do anything but cry. Stop!” says Mother with bitterness and irritation.

“So many years, so many years I protected you, so many years I tried to keep the house, and now I can’t do anything. O God!”

“You were the best of daughters, the best child…always remember this…”

My Father’s words don’t convince me at all.

“You will remain.”

“But without you! – I’ll go where you are going.”

“If Jozio had received a stamp, you would have stayed with him – you’d be two.” My Mother

wanted to save my brother so terribly.

But she knows perfectly well that my brother would not stay without her; she is the driving force

of his impaired nervous system. Only through her can he exist.

Four o’clock. A crowd of disappointed people with unstamped work cards. The Gestapo don’t want

to stamp artisan’s cards. That’s it. I don’t take my Mother’s and brother’s cards, however, because an

acquaintance, a functionary, tells me that even though the Gestapo didn’t stamp any cards today, maybe

by tomorrow morning they could be convinced to do so by “appropriate arguments.”

The Judenrat is having a meeting at this moment….

I see the families of the Judenrat members – that clan ensured against the catastrophe that’s going to

strike us any moment now – quietly milling around the building. I envy them and hate them with my whole heart.

Are they better than my parents? Is there any justice in the world?

German vehicles enter the ghetto. So its now, it’s beginning! I’m preparing myself not to reach home. I notice that the car is driven by a civilian.

“It’s not for us,” I think with relief.

But for what did they come?

It’s the railway and various German enterprises that have sent the vehicles for their workers. They

gave a list of them to the Gestapo. Those people received stamps. And now they have come for them with the

vehicles, to house them in the town during the action.

The sight of these people getting merrily into the car with bundles and children, and the thought that in

a moment they will get out of this hell, drives me to despair. I’m not envious of them: they’re workers; may

God give them all the best. But why couldn’t my brother go with them? Why has fate so horribly persecuted him?

By six everyone must be at home.

I whisper with Dr. Henner for a long time. We stand on the staircase, tired out by this long, horrible

day of feverish, pointless running. He also has elderly parents, and they too are without stamps.

“We’ll all go,” we conclude.

And we are both young, both full of strength, we both want to live… Maybe somehow it can be managed…

We comfort each other without conviction.

Mother is violently washing a few bits of linen and armbands. If we have to go, we have to at least have a change of shirts.

During the night I sleep a heavy, tormented sleep. I dream that I see my Father and brother going along some

grey country road. On the road lies a small boy’s shirt, entirely covered in blood. In the dream I try to keep my

family from passing that bloody rag. My entire life depends, at that moment, on being able to stop them.

“Go back, Tata, go back,” I call out despairingly, but I can’t get the smallest sound out of my throat.

“You’re screaming like a mad woman, at least give me some peace at night.” My Mother shakes me lightly,

“During the day you wail and at night you wake me.”

“Forgive me, Mama, I had such a stupid dream. I won’t tell you. It was strangely monstrous.”

At five my Mother’s cries awaken me: “A car, a car on the square, they’re taking people away, they’re going to take us!!”

Now. The worst has come. What to do? Are they coming from house to house? Mother is terrified, pale.

She packs four bundles and divides a loaf of bread into four parts, so that each of us will have something for the road.

In the quarter there is terror. In the square, through which I have walked so many times, in this square,

now full of barbed wire, the Jews are walking.

Today Jagiellonska and Targowa streets are going. They carry their miserable bundles. Their eyes are full of fear, of terror.

The action surprised them in the night, in their dreams. They were driven here straight from their beds.

The Schutzpolizei have surrounded the square. The vehicles are standing in the street. I can see it all from

our window. The square is 50 metres from our house.

What are they doing?

The young are being placed in groups of four. The older people are being loaded into the vehicles.

“Get away from the windows! Close the windows!” The Gestapo run into our little street. Terrified, I run

away from the window. I hear some shots, the clatter of motors starting up, German, a hoarse shriek. Then quiet.

A quiet that rings in my ears.

Carefully, I look out the window. On the square no one is left, only the Germans from the Construction

Service, youth labour brigade workers with their caps aslant, pulling things off the square: those unfortunate

people had their coats and bundles taken from them. The labour brigade search the things, they are pleased

and make comments: “Well, now these swine got a good lesson, that will cure them of trade and speculation.”

I run out into the street. I don’t stay in the house, in spite of my Father’s pleas. Maybe I can find

something out. Maybe I can arrange something.

The Germans are already carting the furniture of the transported Jews to the empty Water

Mains administration building.

What was yesterday still someone’s property, the fruit of long years of work, is today ownerless,

neglected, overturned, lying on the sidewalk. The labour brigade look in all the cupboards.

And our poor furniture will soon stand here too, I think with despair.

In the Judenrat, it’s a boiler-house, like yesterday. Acquaintances talk about hiding, about how the

old people were taken to the cemetery this morning and shot there. I don’t believe it…

The soup kitchen is working non-stop, but I can’t work there. When I’m there for a moment, my heart pulls me home.

I run home in the fear that they might have been taken in my absence. I call loudly through the window: “Mama! Mama!”

They’re here! I’m saved again.

Tata and I talk continually about the resettlement. I am absolutely decided to go with them.

I can’t imagine that it could be otherwise.

I lie beside my Father on the bed, my arm around his neck. I always lay like this beside him, when I was

a little girl. And then he told me the never-ending story about the brave daughter of the tailor Farjan.

My Father always attributed to the daughter of the tailor Farjan those qualities that he would someday like to see in me.

My Father talks to me about his youth. It was difficult and stormy and he doesn’t like to talk about it.

He lost his mother early, was raised by a step-mother, and suffered a lot. What he got from those years

was a feeling for the essence of life: that it’s a continual struggle.

“Tata, why all this philosophy? I’m going with you. If we’re going to fight, it won’t be alone.”

“You will stay,” says Father firmly, “it will all be easier for me if I know that you will remain after me.”

“Tata, Tata,” I cry terribly. This crying takes away all my strength, and in my mind nothing is left but a large, painful emptiness.

In the ghetto the madness of the German terror reigns. Here 5 persons were shot, there 10, here a German

soldier kicked a grey-bearded old man to death. On the wall adjacent to the small lot on Czarnieckiego

Street red-grey stains are visible. Here the other day during the first transportation 10 older women were shot.

I walk like a lost person. I can see that this will happen to us any day… that there is no salvation for us.

Mama timidly talks of hiding. “Never!” – Father doesn’t want to hear of it. The thuggish propaganda apparatus

has frightened people well. The ordners meetings have put everyone in the right frame of mind.

“They’re to shoot me in my own home? Never.”

Mother won’t leave Father alone. Jozio won’t stay without Mother. Tough. We’ve lost. We’ll all go.

Dr. Henner has decided to go with his parents. Their rich apartment with its cuckoo clock, that I liked

so much, is now sad and empty. Old Henner is pedantically packing his suitcase. “We have to be ready for the road.”

‘It’ could happen even today.

‘It’ hangs over our heads horribly through sleepless nights full of tense expectation.

Our street will certainly go in the next action, unless a miracle happens. Every evening I beg God

long and fervently to save us and every night, when I fall asleep for a while, I dream, as if from sheer spite,

of my happy, irrecoverable childhood. Full of despair, I awake to reality; I sit semi-conscious on the bed and I listen.

Only people with stamps go out into the streets now. The sight of men my Father’s age – and like my

Father unable to work – ostentatiously carrying stamped ZSS identity documents, drives me wild. I

am full of hatred for the world and for people.

The ghetto is now a gallows, from whence everything good and humane has departed.

There are no friends, no acquaintances. The primordial instinct for life, now, when that life is threatened,

has torn the mask of convention from people’s faces and shows their primitive, animal egoism. The rich,

who did not manage to get stamps, are trying to buy them together with the identity documents – and the lives –

of the poor on whom fortune has smiled.

Dr. Tennenbaum’s wife comes to us and says that she heard that although I have a stamp, I want to

go with my parents. She has a cousin, a young girl, who looks like me. She offers to give me 10,000 zlotys if

I give her my identity documents.

“I’m not trading my daughter’s life,” Tata answers proudly, “It is my wish that my daughter remain.”

Mrs. Tennenbaum is clearly embarrassed. She explains that she only wanted the best.

“If Miss Lesia stays, we’ll take care of her.”

I don’t want her care and I don’t want to stay.

I know that Mother, although she doesn’t say so aloud, very much wants me to go. “Somewhere

among strangers, it will be easier if we are together.”

But Father doesn’t allow her even to speak her wish aloud, because it seems that young girls

work in one place, and older women somewhere else.

A thousand rumours are circulating about where we are going. The Judenrat and Duldig take

care that the rumours aren’t terrifying. On the contrary, they dress them up a little: to a village, to an

organized camp for Jews beyond Lwow, managed by a directorate chosen from among decent Jews.

Clever propaganda has done its job for the Hitlerite thugs. Whole gangs rove around the ghetto, shooting and robbing people.

I don’t go to work in the soup kitchen. What for? They’re saying anyway that tonight it will be the turn of our street.

Today several German work sites took away their workers’ red work cards – which were treated by the

Gestapo as if they were stamps. And again there are a thousand condemned persons. And they run around the

Judenrat explaining and imploring.

30 July. Evening. The Judenrat calls the Jewish population together. We crowd into the streets,

anxious to know what we will be told.

Duldig stands in the window on the second floor and makes an ardent speech asking everyone,

as one man, to gather on the square. All those, that is, without stamps. They are going to work. The artisans

will receive jobs in their specialties. But they have to go!

People cry. No one wants to leave even the most miserable home – leave their nearest relations –

and go off into the unknown. We don’t know anything yet about going to certain death.

“Let it happen at last,” says Mother in a tired voice, “I’ve no strength left…”

And yet she takes care of us until the last moment. And when the ordner comes in the night to

hang up the final judgment, that tomorrow morning our street is going, that it’s the end, I find Mother

baking crude biscuits out of black flour on the stove and cooking borsht. “Tata must have something

warm in the morning, you know, he can’t get up so early.”

How brave, how active my Mother is!

All my energy has drained away. Mama packs small bags for all of us: a shirt, a towel, a comb,

and four slices of bread. There’s nothing in the house. No money, no supplies. It was so easy to divide

up our poor property. I don’t make my bed.

“It’s not worth it. They’ll chase us out in a moment anyway.”

She lies down beside me on my bed. We neither of us undress. I put both arms around her.

She is small and slender. She doesn’t say anything, but her warm tears fall on my cheek and set my heart on fire.

“My little birdie, my poor little birdie,” she whispers. I don’t know what to say to her. There is no consolation left here.

My Father and brother are sleeping.

“Stay,” whispers my mother. “Maybe we will come back, maybe we will write and you’ll need to

send us something. I don’t have the strength to persuade you, but listen to me, Lesia – stay.”

I hold my Mother in my arms and tearfully we fall into a short, nervous sleep.

In the morning – it’s dawn outside – a swarm of ordners, a swarm of thugs from the Gestapo,

run into our street. The Gestapo have dogs on leashes. The ordners come into our house. “We’re

coming, we’re coming,” says my Father. He is neatly dressed, shaven. His eyes have a strange light in

them. He hasn’t looked so young for a long time.

And Mother is strangely beautiful today, like in the best times. She has put on a little rouge

because they say that young women get better jobs.

We take our bundles, but it’s hard to leave the house. I take my parcel, but the moment I

take it into my hand I feel that something strange is happening with me. Some resistance is growing in

me from second to second. I don’t want to. I don’t want to go.

Lord, what’s happening to me?

I can’t imagine life without them.

What’s happening to me?

The Gestapo bang on our window.

“We’re coming,” says Tata, “Here you are, my watch, it will stay with you.” He puts the old watch that was his father’s down on the buffet.

“Think that you were with us on a ship during a wreck, and we went down, while a life buoy brought you to shore...”

“Uncle will ask you to Africa after the war,” Mother adds.

Here is the most disinterested, sublime love in the world. Even now my parents don’t think of themselves.

“I’ll accompany you to the square,” I say softly, without looking at my Mother. I know that she was

counting on my going with them, and now I’m leaving her alone, at the worst time…

We go out of our room…

Mother, crying, bends down and kisses the sill.

“After such suffering,” she whispers, “after such awful suffering… into exile again. Oh, the scoundrels.

Accursed, cursed torturers! May no ground receive them. May the entire world’s insects eat them alive for forcing

my family – innocent, quiet people – to go out today into the unknown, to the worst of fates!”

We go to the square. People are coming from all sides, carrying bundles and coats in their arms. So many people… so many people.

“Go back,” my Father says threateningly.

He doesn’t need to repeat it. Some superior strength is pulling me away from this square.

I go back home. I’ll bring a folding chair for Tata.

Amongst the Gestapo agents on the square I see Müller, a pot-bellied thug, who arrested me in

the winter for studying in secret because of information he received from my former landlady, the railway

agent Totowa. But he only kept me a couple of hours, and treated me quite humanely for some reason.

I go up to him and ask him to release my parents from the action. Father was an Austrian officer, he’s ill – I grab at any argument.

“They’re going to work, nothing will happen to them.”

A labour brigader from the Baudienst pulls me away from him.

“Jewess, how can you be so conscienceless, to talk to a Gestapo agent on the square…” he chortles cynically in my ear.

I go home and come back without the chair. I have a stamp, I can move about freely. I come

up to the barbed wire surrounding this square of horror. The Germans are counting people now. They’ve

ordered them to kneel. Mother points me out to Father. I look – she’s so pale, so wretched. Mother rises

from her kneeling position; she wants to come to me. My brother cries “Lesia!” At that moment a German

strikes her on the arm with a whip. Mother’s eyes are terrified. She won’t come to me now. She returns to her

place and kneels again beside Father. By sign language they tell me that they are thirsty.

If I went to the end of the world, I could not erase from my heart that cry of my brother’s – “Lesia!” It was the last word I heard from him.

No image will ever erase the expression in my Mother’s eyes when the German struck her.

I run home for something to drink. Clouds cover the sky; it’s grey.

In the room it’s quiet. Tata’s watch ticks on the buffet. On the iron cooker there are the remains of the

borsht that Mama was still cooking. What shall I bring them?

I go to Dr. E., who lives in the next house. I go through the kitchen. The body of his elderly mother is lying there.

The doctor gave her a fatal injection so that she would die in her bed. I go past her without any feeling.

The doctor gives me a bottle of water with juice. I run with it to the square. I meet an ordner.

“My parents asked for water.”

Lord, couldn’t I have thought of it myself? Did I need to be reminded that they would be thirsty? I run.

Their place is empty…They’ve gone. No, I’ve made a mistake, I was looking in the wrong group. Via the ordner

I give them the water. Tata drinks eagerly. He raises his head and says clearly, “Child, go home.”

Father is afraid that I will go with them. Yesterday, after all, I promised Mother that I would go with her,

and today something is holding me back; I know that I am not going with them. Only later, much later, did I

realize that it was the animal instinct for life – stronger than anything, stronger even than love for one’s parents – that made me stay.

The Germans are shouting something, ordering something. The crowd rises from its knees.

Mama helps my Father to stand. It’s quiet, horribly quiet. The first eight are already moving off. My family

are going too. Tata and Mama raise their hands in my direction. It’s not allowed to say anything anymore. I send them a kiss.

Father is as white as a sheet, but he walks straight. Not for a long time, not since his illness, have I

seen him walk that way. And Mother looks so young. My brother is beside them. His canvas bag stands out

against his dark coat. Father waves his hand at me. And I don’t yet know that I am seeing them for the last time

in my life. I stand by the barbed wire; the square empties; they are taking them to freight cars, at the railway station.

All are walking straight, with proudly raised heads. No one cries. The streets, guarded by Gestapo agents armed to

the teeth, are empty. In the square chairs, glasses, bottles remain. Those who were kneeling a minute ago,

oblivious to everything necessary for life, have gone on their last journey to eternity. Later I often thought that

it must have been on that square that they realized they were being taken not to work, like the

Judenrat had assured them, but to death.

That hellish square is the last focal point of their life; the remainder is an abyss – the abyss of death.

I go home. My mind works with a strange clarity and precision. I realize that my nearest relations have gone

away. I think that I should cry and despair, but the tears don’t come at all from under my lashes. I feel tired.

I sit on a chair by the table. Above the bed hangs a portrait of Mama, young and beautiful, from the time of her

engagement. Tata’s injection lies on his night-table. Who will give him an injection if he has a heart attack on the way?

I open the cupboard; I see some of my brother’s ties.

Germans come into the apartment. They glance around the room and seal the building. With such a search, one could have hidden.

I hear Mama’s timid words: “You know, there was a letter from Tarnopol, there was an action there, they wrote

clearly – ‘when there’s a heat wave, sit in the shade’…So that I would hide…” I realize with horrible certainty that Mother

could have stayed and hidden; Father could have gone alone. But I – I didn’t allow her: “What, do you want to let

Father and Jozio go alone? I’m going with them.” And I didn’t go. I stayed, to take care of our poor house, to wait for

some sign from them, so that they would know that there is some point in the world to which they could return.

This quick check has filled me with despair. Oh, if they had only searched, looked everywhere, so that I

could justify myself in my own conscience, that they couldn’t have stayed!

Mrs. Tennenbaum sends for me upstairs. I run away from the lonely apartment. On the exterior door I

see a small card with a round stamp, “gestempelt durch Sicherheitspolizei”.

The green crew have already left the building. That small card on the door of my empty apartment is a time

piece left from my loved ones. Because they didn’t have that disgusting mark, that stamp on the edge of a paper,

Hitler drove them from their homes into the unknown. I didn’t yet realize that that biggest scoundrel in the

world had driven them out of life…

I go upstairs to Mrs Tennenbaum. Life is bustling at her place. In the kitchen a fire is burning under the

plate. Cake-mix lies on the board, her small son is playing at horses. In a word, a picture of family life.

“You see, I’m preparing a package for my parents, I’ve hidden them.”

“You’ve hidden them? Where? Why didn’t you tell me that it was possible?”

“I was supposed to tell you?” she snaps back, “Are you a child? You should have thought of it yourself.”

Yes, she’s right. I didn’t think; I thought little. I only cried and didn’t do anything for them. And now they’ve gone.

Rain is coming down, striking on the windows of the porch. I look at the square, which, empty now,

refreshed by the rain, is blooming with summer greenery, in spite of everything to which it was recently witness.

A group of youngsters from the Baudienst are searching through the things left on the square. Hyenas.

I look with envy at Mrs. Tennenbaum baking cake for her parents. I feel the lowest sort of envy.

What, are her parents better than mine? No. Only she’s a better daughter than I.

The action is over for today. People – stamped exemplars in armbands - wander through the streets.

The ordners say: here a hiding place was uncovered and 10 people were shot, here 15, etc.

None of it makes any impression on me. I’m thinking only about my family. Maybe it was better that they went.

They will be settled somewhere, they’ll work. We’re so inventive comforting ourselves, so full of defences,

as we never manage to be for our nearest relations.

The rain stops falling. The sun burns down mercilessly. I think of Tata, who can’t stand the heat.

Mother and I always keep him in the house in the afternoon, in a cool room. And he hasn’t been in a train

for so many years. How will he survive, how…?

I feel an animal hunger. I simply gobble the bean soup that Mrs Tennenbaum gives me. I eat it, knowing

that my family have only a piece of dry bread to eat.

Mrs Tennenbaum is still busy preparing the package; she puts in candles, and gives me three as well.

“What for – the day is so long now?”

“Yes, but we can light them together, for our families.”

I don’t understand the sense of these words. I take the candles automatically.

Someone rings. I open the door. Two children come in: red-haired twins, of about six years

of age, I think. A boy and a girl. Well-dressed, with a letter in their hands. Mrs Tennenbaum knows them.

“Witek, Halina, what are you doing here?”

The children have black stockings on their legs and black bands on their arms.

Mrs. Tennenbaum reads the letter aloud: “Dear Tusia, We were always friends. Today I am going

with my husband. The children are orphans from today. Send them to Tarnow, to my sister. You

know her address. Halina has two rings for the road. Take care of my children, of my dearest treasures.

It’s so hard for me to leave them. Good-bye, thank you for everything. Your unfortunate Hela.” I look

through the window and for the first time today I cry. Now I understand why the children are wearing

mourning bands. It was their mother’s despair, dressing the children in mourning for herself.

The children are perplexed, serious. Rysio Tennenbaum goes up to them and after a moment they’re playing.

Mrs. Tennenbaum gives them cookies and cake. The children don’t even ask about their mother. The current

of life carries them on. But that current will be bad, and the undertow treacherous. These children in armbands

are going somewhere into the unknown. Mrs. Tennenbaum is already thinking of a Polish railwayman who

will take them to a safe place, supposedly.

Her husband comes back from the town, from the Employment Department. “This night,” he says, “they’re going to

go around the houses, they’re going to check the children.”

“So Miss Lesia will take Witek to her house, and Halinka will be our daughter.”

“All right, I’ll take Witek home.”

Evening falls. I have to leave them and go home. The sub-tenants have come back. One party, the

upholsterer with a wife and daughter, went to the Kreishauptmann himself. Ludka Wasser, a young, pretty

woman with two sons, has also come back. At the last moment she arranged a fictitious marriage with

her brother-in-law. He had a stamp. It protected her and her two sons. Both parties are cooking, the light is on.

Yes, life has not died down for them, as it has for me.

Only in my room is it so dark and empty. The little photograph of Mama is pale between the windows.

Tata’s watch has stopped ticking. I don’t know how to wind it. Because that’s the way it was with us; only Tata